In 1770, the Billettes religious community dreamt of turning their land into a source of income. Their plan? To build a grand town house, known as an “hôtel particulier,” that they could rent out. The leaseholders, the Count and Countess du Châtelet, had a clear vision for this project. They chose the architect Maturin Cherpitel (1736-1809) to bring their dream to life. From 1770 to 1776, Cherpitel skillfully crafted one of the most stunning hotels in the fashionable Saint-Germain district, a masterpiece of the early Louis XVI style.

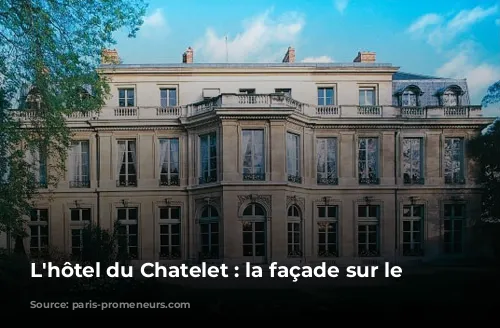

A Majestic Façade

The front of the building facing the courtyard was a breathtaking spectacle, a clear nod to the classical style popularized by architect Ange-Jacques Gabriel in the Petit Trianon and the hotels lining the Place de la Concorde. A colossal portico adorned with Corinthian columns dominated the facade. Above, a balustrade capped with ornate pots-à-feu crowned the structure. This distinctive attic level, with its elegant rooftop, would be a popular architectural feature in France throughout the late 18th century. To the sides of the courtyard, functional outbuildings housed kitchens, stables, and storage spaces.

A Garden View Fit for Royalty

The garden facade of the hôtel was considered one of the most beautiful examples of Parisian architecture in the 18th century. A striking contrast emerged between the straight lines of the attic and the curved shape of the avant-corps, a projecting part of the building. The ground floor featured elaborately carved keystones above the windows, a testament to the craftsmanship of the time. The avant-corps showcased elegant arch-shaped windows adorned with delicate foliage, a distinct departure from the rectangular windows found elsewhere on the facade.

Interiors Fit for a King

The interior of the hôtel was a dazzling spectacle. The grand staircase featured fluted pilasters and niches housing replicas of ancient sculptures. The salon de compagnie, with its angled walls, boasted exquisite ivory and gold woodwork, showcasing the return to classical styles with its Corinthian pilasters, vases, cornucopias, arabesques, and palmettes. This room is now the Minister’s office. The dining room, painted a calming off-white, was oval in shape and graced with garlands of flowers and Ionic pilasters. It culminated in a half-circle adorned with two beautiful marble fountains, their surfaces carved with playful dolphins and intricate foliage.

The Du Châtelet Family: From Grandeur to Tragedy

The Count du Châtelet, son of the renowned Voltaire patron Emilie du Châtelet, embarked on a military career. His path was briefly interrupted by a stint in diplomacy. After inheriting the title of Duke in 1772, he rose through the ranks to become a lieutenant general and then colonel of the French Guards. In 1789, he was elected to represent the nobility at the Estates General, the French parliament before the revolution. Sadly, his life ended in tragedy, as he was guillotined in 1794 during the Reign of Terror.

A Home for Power: The Hôtel du Châtelet through the Ages

The Hôtel du Châtelet continued to witness the ebb and flow of power in France after the Revolution. From 1796 to 1806, it served as a home for the École des Ponts et Chaussées, a prestigious engineering school. Under the Empire, it became the residence of Napoleon’s intendant, and later, during the Restoration, it housed the intendant of King Louis XVIII. A series of prominent figures occupied the hôtel, including Count Daru, the Duke of Cadore, Count de Blacas, Count de Lauriston, and the Duke of Doudeauville.

From 1835 to 1848, the hôtel served as the residence of the Ottoman ambassador, followed by a brief stint as the home of the Austrian ambassador. In 1849, the French government purchased the hôtel, transforming it into the Archbishop’s Palace. After the separation of church and state in 1905, the building became the home of the Ministry of Labor. Today, it continues to serve as the headquarters of the Ministry of Labor, Employment, Vocational Training, and Social Dialogue.

The Hôtel du Châtelet stands as a testament to the rich history of France, from its glorious aristocratic past to its modern role as a center of government. Its elegant architecture, intricate details, and storied history make it a true Parisian gem.