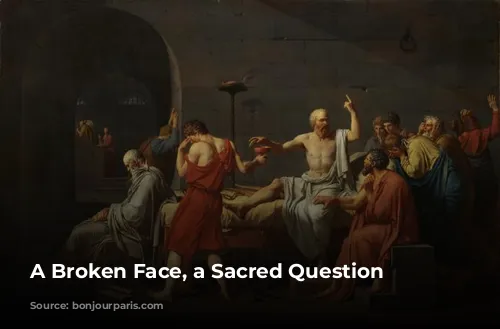

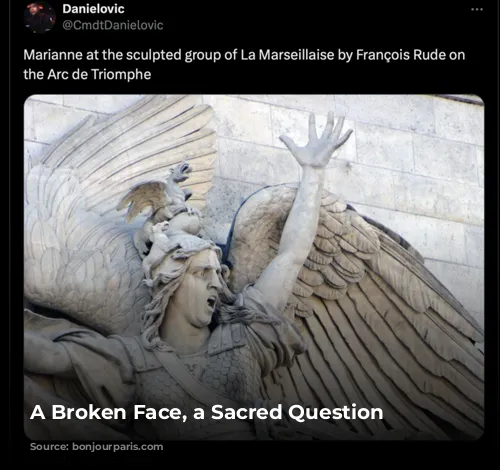

The Arc de Triomphe, a symbol of French pride, bore the brunt of a protest in 2018. “Gilets Jaunes” protestors vandalized the statue of the Marseillaise, leaving a gaping hole in her face. This act of defiance resonated globally, with newspapers showcasing the damaged statue as a grim reflection of the turmoil plaguing France. While authorities vowed retribution, the symbolic destruction seemed to ironically silence the statue’s message of unity and freedom.

The protests faded, and France moved on. The statue was repaired, and the nation’s dignity restored.

The Return of a Sacred Wound

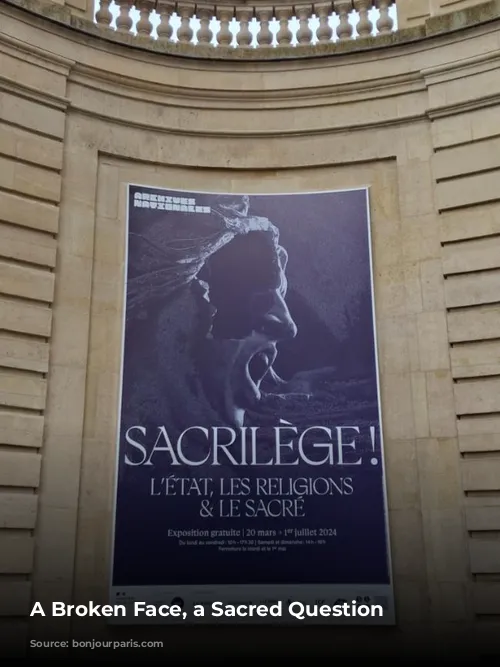

Six years later, the Marseillaise’s broken face found a new home – the National Archives of France. This time, her presence served a different purpose. She was part of a compelling exhibition, “Sacrilège: The State, Religions, and the Sacred,” which explored the age-old conflict between the sacred and the profane. The exhibition challenged viewers to contemplate the meaning of sacrilege and why it remains a potent force throughout history.

A Medieval Preoccupation with Unity

The condemnation of sacrilege, while less prevalent in antiquity, took root during the Middle Ages. This era was marked by a deep conviction that societal stability hinged on a unified belief system. This ideology was so deeply ingrained that even the Knights Templar, protectors of the holy land, faced accusations of heresy. One document on display, dating back to 1307, details the Inquisition against the Knights Templar.

The King’s Crusade for Unity

French kings embraced the idea of a unified belief system with fervor. Pope Innocent III, aiming for a utopian kingdom, initiated a crusade against the Cathars, a dissenting Catholic group, in southern France. While the King embraced this crusade, Pope Clement IV, in 1268, urged the king to ease the persecution. The actual papal bull, or religious decree, issued by Clement IV, is a testament to the complex relationship between faith and power.

The Sacred Under Siege

The exhibition illustrated that the emergence of centralized states, fueled by royal power, led to the creation of a rigid boundary around the sacred. This sacred terrain encompassed concepts like royal authority, the Catholic Church’s doctrine, the divine order of society, and anything perceived as questioning authority. The exhibition highlighted blasphemy as the key term defining the divide between the sacred and the profane.

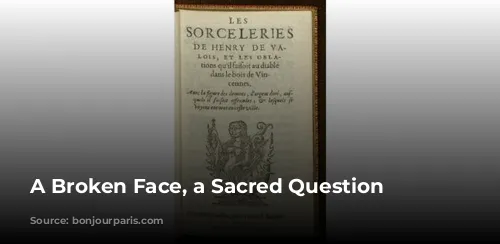

The Reformation era saw the escalation of blasphemy accusations. For Catholic powers, everything Protestant was considered blasphemous, and vice versa. This fueled hatred and justified violence, fueled by propaganda. A stark example of this was the book, Les Sorceleries de Henri de Valois (The Sorceries of Henri of Valois), which accused Henri III of heresy and depicted him as a monstrous hybrid of lion, woman, and Machiavelli.

The Blasphemer’s End

While blasphemy accusations became less frequent over time, the last recorded death sentence for blasphemy in France occurred in 1766. The Chevalier de la Barre, convicted of minor transgressions against religious customs, was beheaded. His full letter of condemnation is displayed in the exhibition. This case sparked outrage, including from Voltaire, who pointed out the absurdity of punishing blasphemy in an increasingly enlightened era.

From Blasphemy to Sacralized State

While the Enlightenment seemingly rendered blasphemy obsolete, the exhibition’s organizers remind us that the concept of sacrilege never truly ended. Instead, governments simply shifted their definition of the sacred. France ceased prosecuting religious crimes and instead deemed the state, and its leaders, as sacred. This is evident in an 1814 declaration that declared the king “inviolable and sacred.” In 1830, a cartoonist faced numerous lawsuits for depicting King Louis-Philippe as a pear.

The Continuing Debate

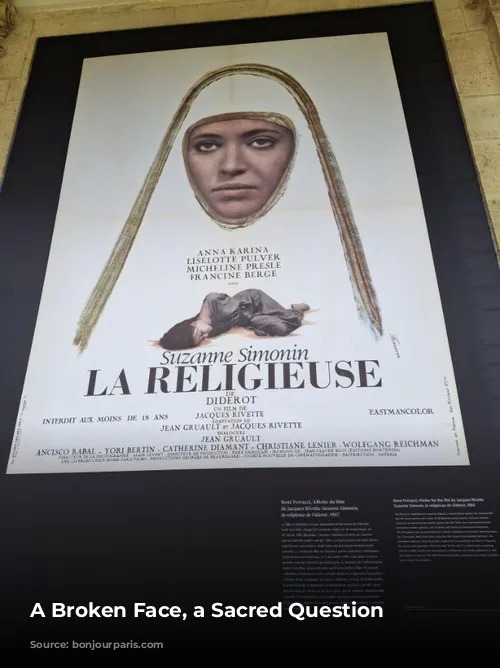

As the exhibition delves into the 20th century, it grapples with the ongoing tensions surrounding the sacred. Questions arise about the limits of free speech, the boundaries of personal offenses, and whether artistic works should face condemnation for their satirical or truthful portrayals of the sacred.

Diderot’s novel, La Religiuese (The Nun), adapted into a film by Jacques Rivette and Jean Gruault in 1965, sparked public outcry and censorship. The film’s ban was itself censored on French television. This incident serves as a reminder that the conflict between the sacred and the profane remains a potent force, even in modern times. The broken face of the Marseillaise, a symbol of both defiance and resilience, stands as a testament to this ongoing debate.