The 1889 World’s Fair in Paris, a grand spectacle celebrating the 100th anniversary of the French Revolution, was a testament to France’s resurgence. The event, masterminded by renowned engineer Jean-Charles Alphand, a close associate of Baron Haussmann, aimed to showcase the nation’s achievements after a period of turmoil.

The fair was divided into distinct sections, each highlighting a different facet of French ingenuity and progress. The Esplanade des Invalides hosted exhibits dedicated to the country’s colonial endeavors and military might. Meanwhile, the Champs de Mars and the Palais du Trocadéro became bustling centers for showcasing the advancements in art and industry.

A Nation’s Rebirth

The exhibition served as a powerful statement of France’s renewed strength. A replica of the Bastille, a symbol of the revolution, stood as a reminder of the nation’s turbulent past. The fair boasted impressive displays of France’s burgeoning colonial empire, its thriving industrial sector, and its return to the ranks of European powerhouses.

However, the event was met with skepticism from European monarchies, leading to a notable absence of their pavilions. Undeterred, the organizers embraced a broader scope, presenting a fascinating journey through human civilization. Visitors were captivated by reconstructions of ancient dwellings, from troglodyte caves to Neolithic lake cities, offering a glimpse into the history of human habitation.

In a pioneering move, the fair dedicated a special Pavilion for Children, a whimsical space designed to entertain young minds. This innovative addition, inspired by the Women’s Pavilion at the Philadelphia World’s Fair, signaled a growing understanding of the importance of engaging children in learning and discovery.

A Triumph of Architectural Innovation

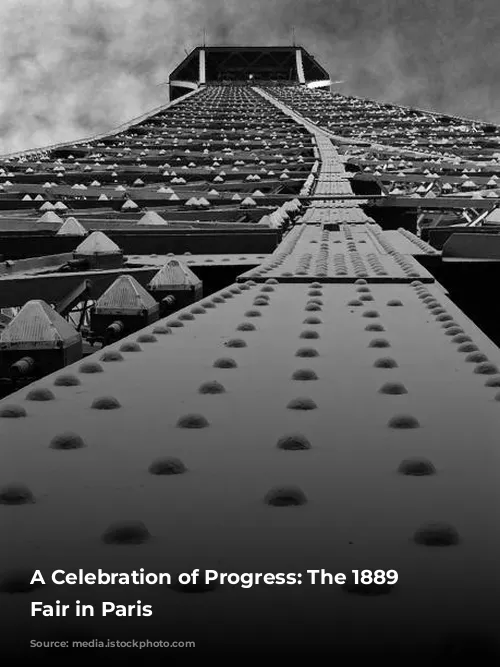

The 1889 World’s Fair is remembered most for its awe-inspiring architecture. The use of metal structures, particularly glass, created innovative architectural forms, ushering in a new era of design. The Palais des Machines, a colossal masterpiece by Dutert and Contamine, was the epitome of this architectural revolution. With a single vault spanning an astonishing 77,000 square meters, the structure resembled a vast, airy cathedral of iron and glass.

Writer Joris-Karl Huysmans marveled at the “exorbitant lancet arch” that “joins under the infinite sky of the windows its prestigious points,” The Palais des Machines was a marvel of engineering, boasting an impressive 35,000 square meters of glass sourced from Saint-Gobain. Visitors were enthralled by displays of cutting-edge technology, including Dayex’s voting machines, atmospheric hammers, cigarette-making machines, and the Tissot clock-making workshop.

The Eiffel Tower: A Symbol of Ambition

A monumental symbol of the fair, the Eiffel Tower, designed by Gustave Eiffel, became an instant sensation. At 324 meters, it was the tallest structure in the world, a testament to the boundless ambitions of the era. Despite facing criticism from some artists who deemed it “useless and monstrous,” the tower became a beloved icon. Every night, gas burners illuminated the tower, casting a dazzling glow over the cityscape.

Nearly 2 million visitors, an average of 12,000 per day, ascended the Eiffel Tower, eager to experience the unparalleled panorama of Paris. This was a time when aerial views were still a novelty, and the tower offered a unique perspective on the city.

A Celebration of Progress and Beauty

The fair also showcased the transformative power of technology with the Decauville railway. Inaugurated on May 4, 1889, this 3-kilometer train line connected the Champs de Mars to the Invalides, facilitating transportation across the vast exhibition grounds. The fair was also a spectacle of light, thanks to the ingenuity of Hippolyte Fontaine. He designed the “largest known electric lighting installation,” illuminating the event until midnight, allowing visitors to revel in the wonders on display after dark. The luminous fountain of Coutan, whose colors danced in time with music played by a live band, became an unforgettable highlight of the evening entertainment.

Artistic Flourishing: A New Era of Design

The fair also celebrated the achievements of French decorative arts, showcasing the exquisite craftsmanship of national manufactures. Separate pavilions highlighted ceramics, furniture, goldsmithery, jewelry, and other artistic creations. The Manufacture of Sèvres, under the direction of Carrier-Belleuse, presented a collection of models that redefined the factory’s style.

The Goldmith’s Gallery hosted a dazzling display by Christofle, featuring models by Mercié, Coutan, and Delaplanche. The Art Bronzes Gallery showcased the impressive monumental vase by Rindel d’Illzach, a stunning example of the emerging Symbolist movement. The Furniture Gallery was a showcase of the enduring elegance of Louis XV and Renaissance styles. A cabinet designed by Paul Sédille, carved by Allar, and decorated with enamels by the Symbolist artist Olivier Merson, was awarded a gold medal for its exquisite craftsmanship.

The 1889 World’s Fair marked the emergence of Art Nouveau, a revolutionary artistic style that embraced organic forms and decorative elements. The School of Nancy, a prominent force in the Art Nouveau movement in France, saw many of its members receive recognition at the fair, including Émile Gallé, Émile Friant, and Victor Prouvé.

The 1889 World’s Fair in Paris was a grand celebration of progress, innovation, and beauty. The event showcased France’s remarkable achievements in architecture, technology, art, and industry, leaving an indelible mark on the world.