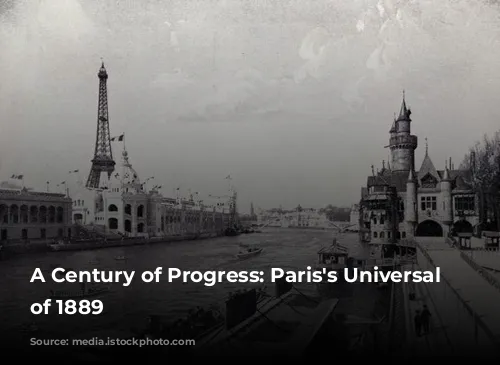

The 1889 Universal Exhibition in Paris was a grand celebration, marking the 100th anniversary of the French Revolution. Just like the 1876 World’s Fair in Philadelphia, this event aimed to showcase advancements in various fields, leaving a lasting impact on the world. The exhibition was meticulously organized by Jean-Charles Alphand, a prominent engineer in the city of Paris and a close associate of Baron Haussmann.

The sprawling exhibition encompassed various locations across the city. The Esplanade des Invalides housed displays from French colonies and the Ministry of War, while Art and Industry took center stage at the Champs de Mars and the Palais du Trocadéro.

A Showcase of Republican Success

The exhibition was not just a display of technological and artistic achievements; it was a symbolic declaration of France’s resurgence after a period of turmoil. Following the Franco-Prussian War, the Paris Commune uprising, and a severe economic crisis, the Republic had emerged strong, boasting a vast colonial empire and a flourishing industrial sector. This display of national strength was a clear message to the world, especially to the European monarchies that had largely boycotted the event.

The exhibition organizers took a unique approach to showcasing human history. They presented a “tour of the world,” featuring architectural marvels from various continents, including a fascinating “history of human habitation,” featuring replicas of prehistoric dwellings like troglodyte caves, neolithic lake cities, and homes of ancient civilizations. This section highlighted the evolution of human ingenuity and adaptation, emphasizing the interconnectedness of humanity across time and space.

Another groundbreaking feature was the dedicated Pavilion for Children, a pioneering initiative inspired by the Philadelphia Women’s Pavilion of 1876. This was a testament to the exhibition’s commitment to inclusivity and engagement, aiming to entertain and educate young audiences.

A Triumph of Metal and Glass

The 1889 Universal Exhibition is best remembered for its architectural feats, particularly the striking use of metal and glass. These innovative materials allowed for the creation of bold, new architectural forms, pushing the boundaries of design and engineering.

The exhibition’s most iconic structure was the Palais des Machines, designed by Dutert and Contamine. This monumental building, spanning a remarkable 77,000 square meters, featured a single vault and a vast nave, making it a true engineering marvel. The “exorbitant lancet arch” described by Huysmans, with its 35,000 square meters of glass, was a testament to the era’s innovative spirit.

Within the exhibition, visitors were awestruck by displays of cutting-edge technologies. Dayex’s voting machines, atmospheric hammers, cigarette-making machines, Tissot’s clockmaking workshop, phonographs, and telephones showcased the rapid pace of technological advancement and the dawn of a new industrial age.

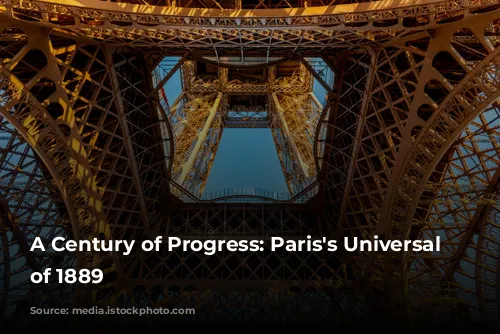

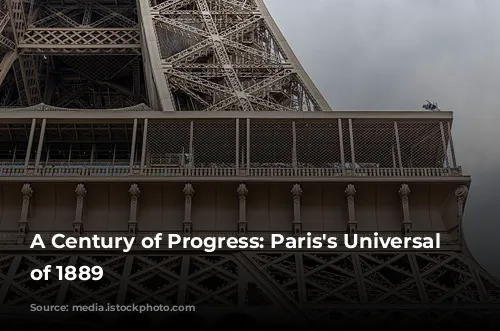

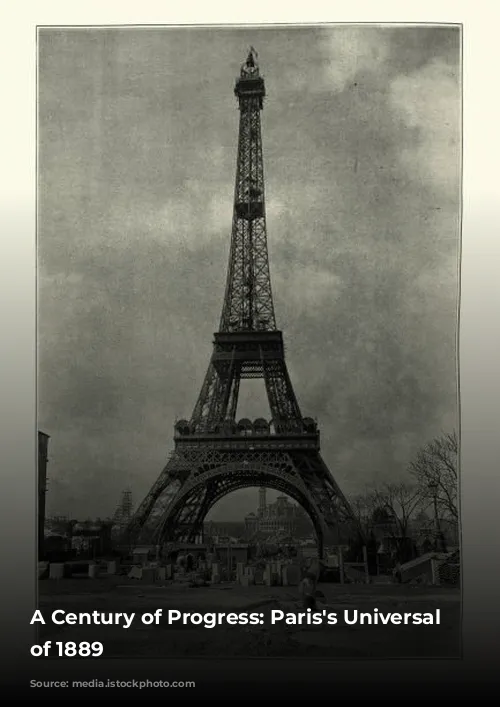

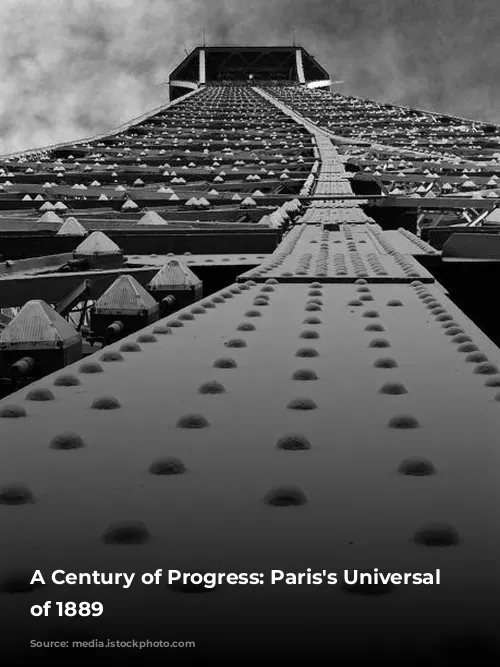

The Eiffel Tower: A Monumental Symbol

But arguably the most enduring symbol of the 1889 exhibition is the Eiffel Tower, a towering feat of engineering by Gustave Eiffel. Standing tall at 324 meters, it was the world’s tallest monument at the time. While the project faced opposition from some artists and intellectuals who deemed it an eyesore, the tower quickly became a symbol of Paris and a must-see attraction.

Every night, gas burners illuminated the tower, casting a mesmerizing glow across the city. Over two million visitors ascended the tower during the exhibition, an average of 12,000 per day, drawn to the breathtaking panoramic views of Paris from its upper floors. The Eiffel Tower, a controversial structure at its inception, has become an enduring icon, symbolizing the spirit of innovation and progress that defined the 1889 exhibition.

Innovations in Transportation and Lighting

Beyond its architectural wonders, the exhibition featured groundbreaking innovations in transportation and lighting. The Decauville railway, a symbol of 19th-century progress, transported visitors over a three-kilometer route between the Champs de Mars and the Invalides.

The exhibition was also a pioneer in electric lighting, with Hippolyte Fontaine creating the “largest known electric lighting installation,” allowing the event to remain open until midnight. The luminous fountain of Coutan, which changed colors in sync with musical performances, was a captivating spectacle, showcasing the harmonious blend of technology and artistry.

Celebrating Decorative Arts

The 1889 Universal Exhibition not only showcased technological advancements but also celebrated the craftsmanship and creativity of the decorative arts. Several dedicated pavilions displayed the finest examples of National Manufactures, highlighting excellence in ceramics, furniture, goldsmithing, jewelry, and other artistic fields.

The Manufacture of Sèvres, under the direction of Carrier-Belleuse, captivated visitors with its exquisite collection, showcasing a renewed style in pottery and ceramics. At the Goldsmith’s Gallery, Christofle exhibited models by renowned artists Mercié, Coutan, and Delaplanche. The Art Bronzes Gallery featured the striking “monumental vase of Rindel d’Illzach,” inspired by the rising Symbolism movement.

The Furniture Gallery celebrated the enduring elegance of Louis XV and Renaissance styles. A cabinet designed by Paul Sédille, carved by Allar, and decorated with enamels by Olivier Merson, received a prestigious gold medal.

The Emergence of Art Nouveau

The 1889 Universal Exhibition marked a turning point in the artistic landscape. It signaled the emergence of Art Nouveau, a revolutionary movement that sought to break free from traditional styles. The School of Nancy, a leading force in the Art Nouveau movement in France, saw several of its members receive recognition at the exhibition. Emile Gallé, Emile Friant, and Victor Prouvé showcased their distinctive style, heralding the arrival of a new aesthetic that emphasized organic forms, natural motifs, and innovative materials.

In conclusion, the 1889 Universal Exhibition in Paris was more than just a showcase of technological advancements and artistic creations. It was a celebration of France’s national revival, a testament to the power of innovation, and a harbinger of a new era in art and design. Through its architectural feats, its embrace of new technologies, and its dedication to showcasing the best of French artistry, the exhibition left an enduring mark on the world, forever etching itself in the annals of history.