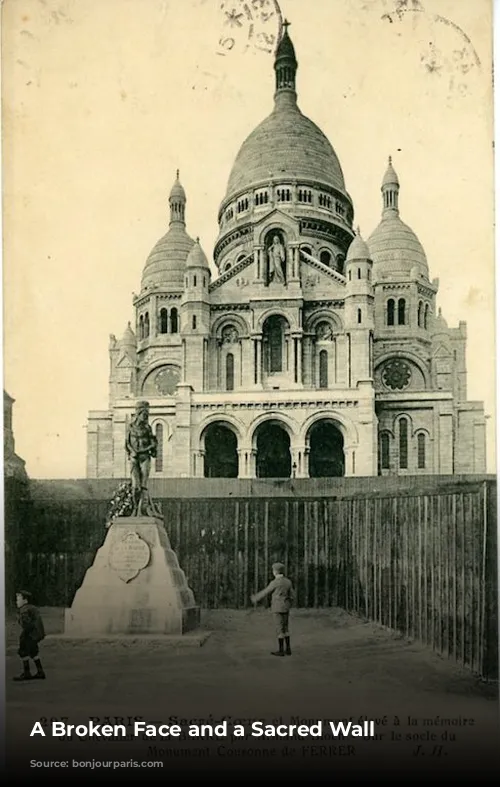

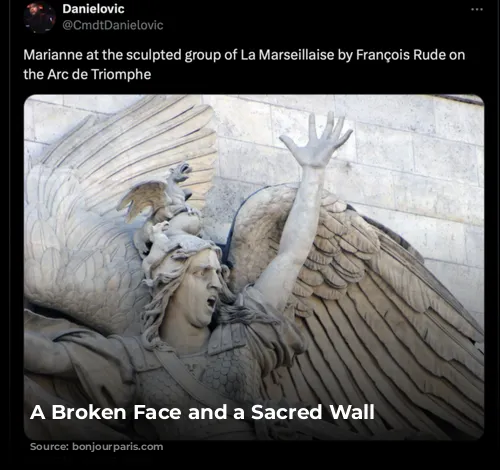

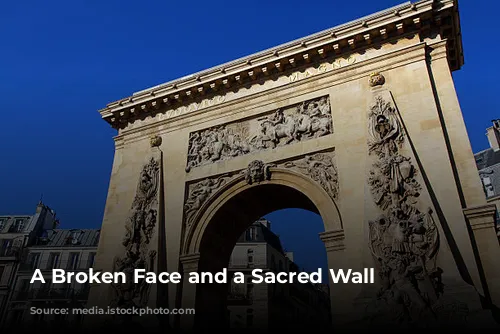

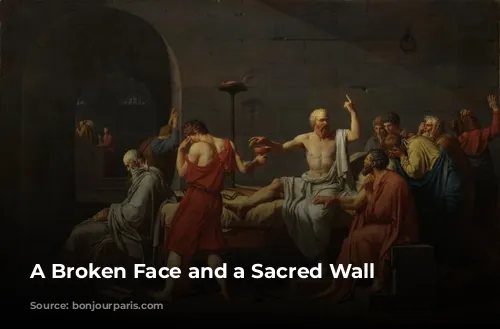

In the heart of Paris, a symbol of France’s rebirth lay broken. On December 1, 2018, the “gilets jaunes” movement, a group of protestors, vandalized the Marseillaise statue inside the Arc de Triomphe. The woman’s head, now bearing a gaping hole, made headlines worldwide. The state vowed to punish the culprits. Ironically, the damage seemed to silence her plea for unity and liberty. Today, the protests have quieted, and the vandals have moved on to other forms of rebellion. The statue was meticulously repaired, and France’s dignity restored.

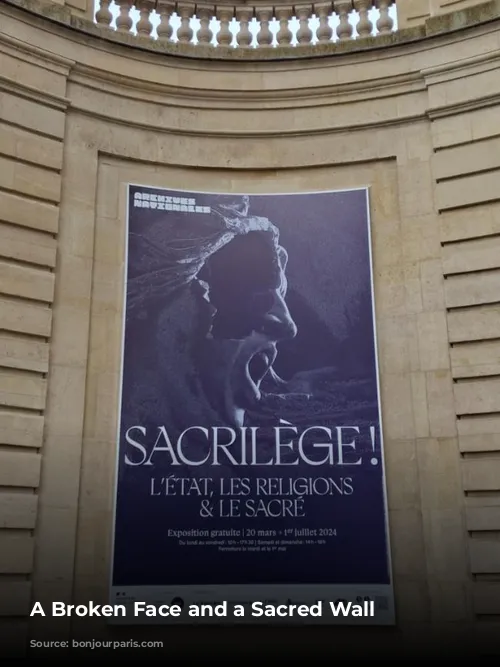

Six years later, the broken face of the Marseillaise resurfaced in an unexpected place. The National Archives of France hosted a captivating exhibit titled “Sacrilège: the State, Religions, and the Sacred.” This remarkable exhibition, filled with compelling images, delved into a persistent theme in human history: the ongoing conflict between the sacred and the profane. It challenges us to contemplate the enduring power of sacrilege.

The Rise of the Sacred and the Profane

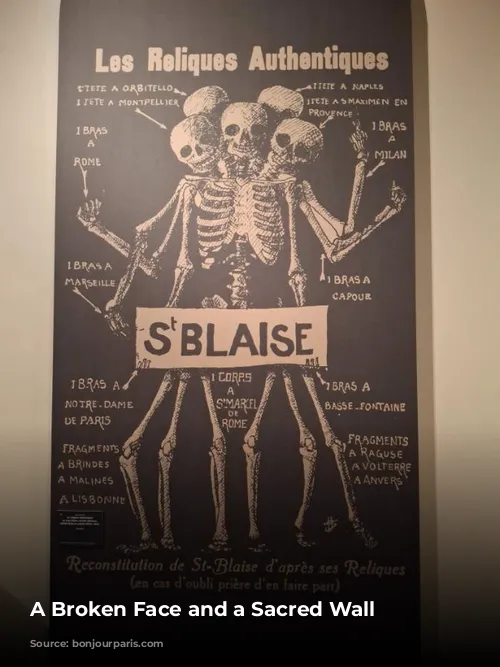

The concept of sacrilege was seldom condemned in ancient times. Its rise to prominence coincided with the Middle Ages. The medieval period saw the emergence of a powerful idea: unity of belief was crucial for a kingdom’s stability. This conviction fueled the persecution of those who dared to deviate from the prevailing faith.

Even the Knights Templar, protectors of the holy city of Jerusalem, became victims of this zealous pursuit of uniformity. Accused of heresy, many Templars were burned alive. A 1307 document, now on display in the Archives, chronicles the devastating inquisition against this once-sacred order.

This obsession with religious homogeneity reached its peak during the Albigensian Crusade. Initiated by Pope Innocent III in 1209, the crusade aimed to eradicate the Cathars, a dissenting Catholic group. The king of France eagerly participated, hoping to achieve a unified realm. However, the relentless persecution drew criticism, prompting Pope Clement IV to issue a papal bull in 1268, urging King Louis IX to temper his zeal. This historical document, also on display in the Archives, reveals the evolving role of the Church in matters of religious freedom.

The Sacred and the State: A Dangerous Alliance

The emergence of centralized states, reliant on royal power, led to a dramatic shift in the definition of the sacred. The “sacred” expanded to encompass royal authority, the truth of the Catholic Church, and any notion challenging established power. Under these newly formed kingdoms, questioning authority became tantamount to sacrilege.

The Church and the State increasingly merged, further blurring the lines between sacred and profane. The term “blasphemy” became a central weapon in this battle for control. During the Reformation, “blasphemy” could encompass all things Protestant to Catholic powers, and vice versa. Propaganda fueled religious hatred and justified violence. One particularly striking example on display at the exhibit is a small book titled “Les Sorceleries de Henri de Valois,” which depicts King Henri III as a monstrous figure.

Blasphemy and the Evolution of Power

As centuries passed, the persecution of blasphemy gradually declined. However, the infamous case of the Chevalier de la Barre, executed in 1766 for blasphemy, serves as a stark reminder of the enduring power of this offense. His letter of condemnation, on display in the Archives, reveals the absurdity of the charges against him: failing to remove his hat during a religious procession, uttering blasphemies, and showing respect for “impious books.”

Despite the Enlightenment’s rejection of blasphemy, the exhibit’s organizers remind us that its spirit persisted. Governments merely shifted their definition of the sacred. The state itself, and its leaders, became sacred objects, demanding reverence and protection. The exhibit showcases a declaration from 1814 proclaiming the king “inviolable and sacred.” In 1830, a cartoonist faced numerous lawsuits for portraying King Louis-Philippe as a pear.

The exhibit underscores the enduring challenges of balancing free speech with the perceived sanctity of institutions and individuals. It prompts us to consider the boundaries of personal offense and the role of satire in a world where powerful entities can be perceived as untouchable. Diderot’s novel, La Religiuese, banned for its bold critique of religious institutions, serves as a reminder of the fragility of free expression in the face of the sacred.

The exhibit “Sacrilège” offers a powerful and thought-provoking glimpse into the enduring human struggle between faith, authority, and freedom. It invites us to contemplate the evolution of the sacred and its influence on our understanding of power, belief, and individual expression.