The 1889 World’s Fair in Paris was a celebration of the French Revolution’s centennial, just as the Philadelphia World’s Fair of 1876 had commemorated the American Revolution’s centennial. This grand event, expertly directed by Jean-Charles Alphand, a close associate of Baron Haussmann and a prominent engineer in Paris, showcased the nation’s achievements after a tumultuous period.

A Nation Rebuilt

The exhibition was a testament to France’s resilience. After enduring the defeat in the Franco-Prussian War, the turmoil of the Commune, and a severe economic crisis, France had emerged as a powerful industrial nation with a vast colonial empire. This resurgence was evident in the impressive displays of French industry and colonial holdings at the Esplanade des Invalides. The Champs de Mars and the Palais du Trocadéro were filled with exhibits showcasing the arts and industries that were driving France’s progress.

The reconstruction of the Bastille, a symbol of the revolution, was a powerful reminder of the country’s past struggles and its triumphant rise. However, the European monarchies, wary of France’s growing power, largely refused to participate in the exhibition, choosing not to erect pavilions. This absence allowed for a more global perspective, with the exhibition showcasing the architectural heritage of various civilizations through reconstructions of troglodyte caves, neolithic lake cities, and houses from ancient civilizations worldwide. The exhibition also included a Pavilion for Children, a pioneering concept inspired by the Women’s Pavilion at the Philadelphia fair, aimed at entertaining young visitors.

A Celebration of Innovation

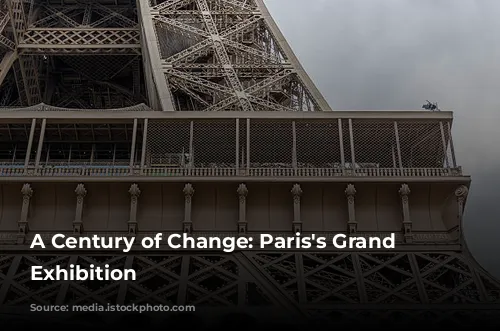

The 1889 World’s Fair was a dazzling display of architectural innovation, particularly in the use of metal structures. The Palais des Machines, designed by Dutert and Contamine, was a breathtaking example of this new approach, featuring a single vault spanning 77,000 square meters and an impressive 35,000 square meters of glass. Joris-Karl Huysmans, a renowned writer, described this architectural marvel as “an exorbitant lancet arch that joins under the infinite sky of the windows its prestigious points.” The fair also showcased the latest technological advancements, with exhibits ranging from Dayex’s voting machines and atmospheric hammers to cigarette-making machines and the Tissot clock-making workshop. Phonographs and telephones, the cutting-edge communication devices of the day, were also featured.

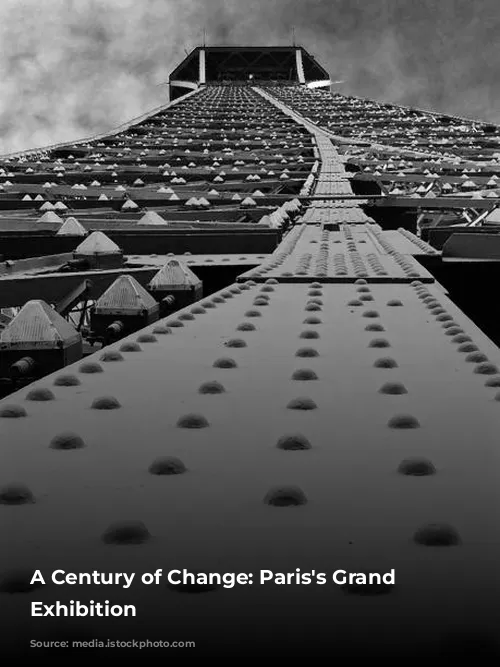

The Iconic Eiffel Tower

The Eiffel Tower, designed by Gustave Eiffel, was the undeniable star of the exhibition. This 324-meter-tall structure, the tallest monument in the world at the time, was a testament to engineering prowess. Despite facing criticism from some artists who considered it “useless and monstrous,” the tower quickly became a beloved icon. Visitors flocked to the tower, with nearly 2 million ascending its heights to enjoy the unprecedented panorama of Paris. The tower’s nighttime illumination with gas burners added a magical touch, making it a captivating spectacle.

A Symphony of Progress

Beyond the Eiffel Tower, the exhibition showcased other innovations of the 19th century, including the Decauville railway, a symbol of the era’s transportation advancements. This 3-kilometer-long railway connected the Champs de Mars with the Invalides, allowing visitors to explore the sprawling exhibition. Hippolyte Fontaine, renowned for his electrical engineering expertise, installed the “largest known electric lighting installation” at the fair, making it possible to enjoy the exhibition’s wonders until midnight. The Coutan luminous fountain, which shimmered and changed color in rhythm with the accompanying music, was another highlight.

Artistic Expression and a New Style

The exhibition also offered a platform for decorative arts, with dedicated pavilions showcasing ceramics, furniture, goldsmithery, jewelry, and other exquisite crafts. The Manufacture of Sèvres, under the direction of Carrier-Belleuse, displayed a remarkable collection of models, revitalizing the factory’s artistic style. The Goldsmith’s Gallery featured works by renowned artists like Mercié, Coutan, and Delaplanche, while the Art Bronzes Gallery showcased the monumental vase by Rindel d’Illzach, an example of Symbolism in art.

The Furniture Gallery was a testament to the enduring beauty of Louis XV and Renaissance styles. A cabinet designed by Paul Sédille, carved by Allar, and decorated with enamels based on the designs of Olivier Merson, a prominent Symbolist artist, earned a gold medal. The exhibition also marked the emergence of Art Nouveau, a groundbreaking artistic movement. The School of Nancy, a leading force in this movement, saw several of its members, including Emile Gallé, Emile Friant, and Victor Prouvé, honored for their innovative work.

The 1889 World’s Fair in Paris was a celebration of France’s resilience, its technological advancements, and its artistic creativity. This grand exhibition showcased the nation’s resurgence after a turbulent period, while also offering a glimpse into the future, foreshadowing the emergence of a new artistic movement that would shape the 20th century.