La Samaritaine, the iconic Parisian department store, is a dazzling spectacle of modern design. Stepping into its top floor, you’re greeted by an artificial beach with a wall-sized digital screen displaying a sunset over a sparkling sea. Downstairs, futuristic face masks glow with red LED light at the “beauty light bar,” promising to rejuvenate your skin. And for those seeking a touch of French history, an immersive Olympic retail experience awaits, featuring stuffed mascots shaped like grinning French revolutionary hats. But amidst all this spectacle, one crucial element is missing: customers.

A Legacy of Luxury and Innovation

La Samaritaine was initially launched in 1870 as a one-stop shop for everything, from lingerie to lawnmowers. In 2001, the luxury conglomerate LVMH acquired the store, embarking on a controversial 16-year, €750 million renovation with Japanese Pritzker prize-winning architects Sanaa. This ambitious project transformed the department store into a five-star hotel, with rooms starting at €2,000 per night.

Despite its luxurious makeover, La Samaritaine struggles to attract shoppers. Tourists may stop to admire the store’s famous art nouveau atrium, but few make a purchase. This is not an isolated case; department stores across the globe are grappling with dwindling footfall, many forced to reimagine themselves as co-working spaces, libraries, apartments, and offices.

A Nostalgic Journey Through Retail History

This forlorn shopping landscape is a far cry from the golden age of Parisian grands magasins. The Musée des Arts Décoratifs, located near La Samaritaine, offers a nostalgic glimpse into the glamorous history of these retail giants. This opulent exhibition evokes the birth of a building type and a cultural phenomenon that revolutionized urban life. It’s a wistful celebration of retail nostalgia, echoing the current Parisian sentimentality for the last time the city hosted the Olympic Games in 1924. Could this historical journey hold the key to reviving struggling department stores?

The Birth of a Consumption Culture

The world’s first department stores were awe-inspiring spectacles. The exhibition features supersized lithographs depicting the grand interiors of these palatial temples of consumption, which emerged in the 1850s during the economic boom of Napoleon III’s Second Empire. Vaulted glass ceilings adorned with gilded chandeliers cast a shimmering light over processional staircases that meandered between cascades of balconies, supported by ornate sculptures.

These cathedrals of commerce, located along the impressive boulevards built during Baron Haussmann’s rebuilding of Paris, were built on a monumental scale. The Crespin-Dufayel store, for instance, spanned over two and a half acres and employed 15,000 people. Inspired by opera houses, these grand spaces were designed as theatrical stage sets for the newly affluent bourgeoisie. Industrialists, bankers, and traders flocked to these spaces to be seen and to display their newly acquired wealth.

A Haven of Leisure and Luxury

These department stores were more than just places to shop; they were designed as havens of leisure and luxury, providing a regal setting for the newly leisured classes to enjoy a day out. Women, for the first time, could relax and socialize in these spaces, away from their husbands, enjoying a newfound sense of independence, as depicted in Émile Zola’s 1883 novel, The Ladies’ Paradise.

Stores welcomed customers as guests, with no pressure to buy, a radical concept at the time. Against these opulent backdrops, store owners perfected the emerging art of product display, strategically juxtaposing items to provoke an irresistible desire for possession.

The Rise of Mass Consumption and Fashion

The department store’s theatrical approach worked, drawing in crowds of eager shoppers. The newly affluent bourgeoisie craved the image of a specific lifestyle, and the department store provided the perfect platform to purchase the complete aristocratic look – from frock coats to dining tables, tea sets, and lampshades.

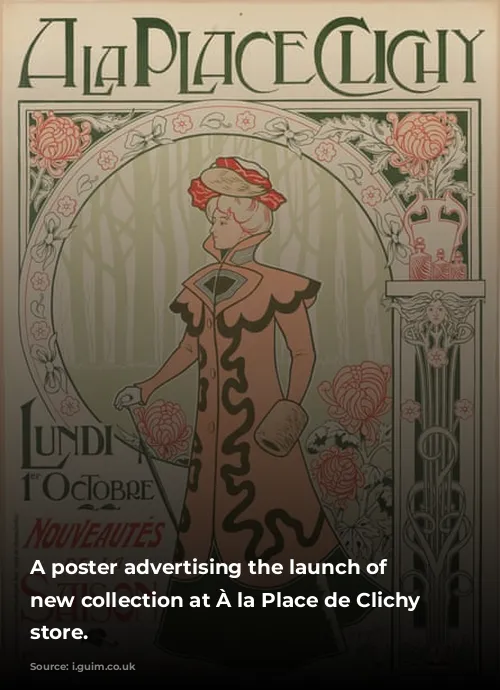

The exhibition highlights the democratization of fashion, fueled by the mechanization of the textile industry. Entire outfits and matching accessories were mass-produced and sold as packages, creating the ready-to-wear look. Advertising posters promoting “La Parisienne” – the epitome of the chic, independent woman – cemented Paris as the global capital of taste.

The Birth of Sales, Marketing, and Fast Fashion

Sales techniques grew increasingly sophisticated, with the invention of “special sales exhibitions” to boost purchases during off-peak seasons. The annual calendar revolved around monthly sales periods, driven by advertising campaigns in the press. This strategy managed the flow of mass-produced merchandise, creating a sense of panic among customers, encouraging them to stay ahead of the latest trends. It marked the dawn of fast fashion, with cases of hastily produced fascinators, fans, neckties, and hats, reminiscent of an antique Asos.

The Dawn of Mail-Order and Subscription Commerce

The exhibition showcases the birth of the mail-order catalogue, featuring beautiful examples from the late 19th century, filled with intricate illustrations of everything from umbrellas and canes to tennis rackets and bicycles. One particularly charming display showcases bathing costumes with matching bonnets from Le Bon Marché. The exhibition also reveals that “subscription commerce” – a forerunner of Amazon’s “Subscribe and Save” – already existed in the 1850s.

The Dark Side of Consumerism

The gaudy display of merchandise and materialism creates an entertaining and enlightening show, but it can also be a bit unsettling. This is where the era of unbridled consumerism began, where marketing methods were refined, sales techniques honed, and the global addiction to acquiring more stuff originated. A section titled “Children As the New Target Market”, charting the history of advertising directly to children, is particularly concerning. A parallel display about the emergence of landfill sites, exploitative supply chains, and the environmental impact of fast fashion and furniture industries would be a valuable addition.

A Call for Transformation

If the department store’s days are numbered, should we mourn its passing? Or could it spark a new vision for urban public spaces? Instead of solely revolving around consumption, these spaces could become vibrant hubs for reading, relaxation, learning, creation, and exchange. Just like the recent wave of expanded libraries across Europe, these multi-story palaces of spending could be transformed into modern living rooms for the city.

The department store’s history is a fascinating exploration of consumerism’s evolution. It teaches us valuable lessons about the past while prompting us to imagine a more sustainable and enriching future for our urban spaces.