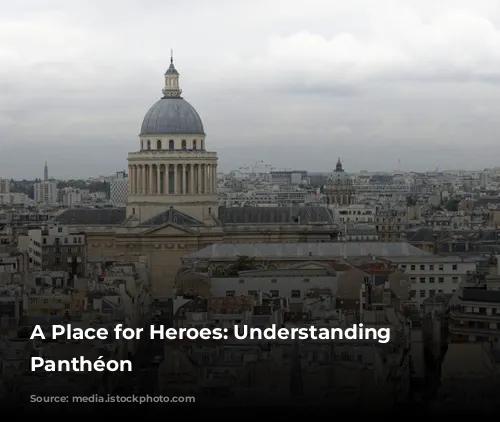

The Panthéon, a magnificent building in the heart of Paris, is more than just a beautiful monument. It’s a symbol of France’s history and a place where the country honors its most significant figures. On February 21, 2024, the Panthéon will welcome two new heroes: Missak and Mélinée Manouchian, Resistance fighters who bravely fought against the Nazi occupation during World War II. Their induction marks a special occasion – the 80th anniversary of Missak Manouchian’s execution.

This is not the first time the Panthéon has seen new additions. In recent years, French President Emmanuel Macron has welcomed several notable figures, including Simone Veil, Maurice Genevoix, and Joséphine Baker. The latest addition, announced after the passing of former justice minister Robert Badinter, will be the man who abolished the death penalty in France.

But how does the selection process work? What exactly makes someone worthy of a place in this grand mausoleum?

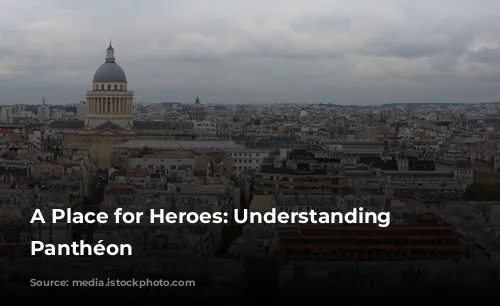

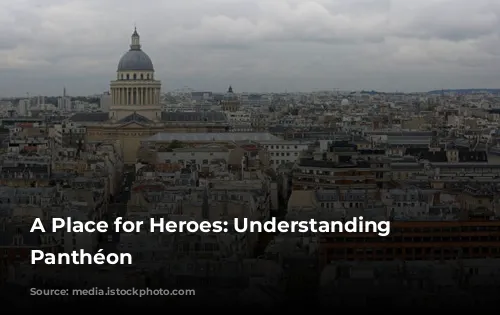

The Panthéon: A Temple for Heroes

The Panthéon’s story began as a church dedicated to Sainte Geneviève, the patron saint of Paris. But during the French Revolution, it transformed into a secular temple, inspired by the Greek Pantheon and dedicated to honoring the country’s new heroes.

The building, designed by architect Germain Soufflot in 1764, was originally intended as a church dedicated to Sainte Geneviève, saint patron of Paris. In 1791, during the French Revolution, the Assemblée Nationale decided to turn it into a secular temple, called “Panthéon” in reference to the Greek gods. It would honor the memory of the country’s new heroes – a republican equivalent of the Saint-Denis Basilica, the necropolis of the kings of France.

This symbol of the French Republic has seen its purpose change throughout history. It became a church again during the 19th century, only to be rededicated as a temple for heroes once more in 1885, during the funeral of writer Victor Hugo.

Who Gets to Be a Hero?

The first to be honored in the Panthéon were revolutionaries like the Count of Mirabeau and the philosopher Voltaire. Over the years, the Panthéon has hosted a diverse range of figures, including military leaders, scientists, writers, and politicians. Notably, many of the early inductees were military men and dignitaries, but the focus shifted as time passed.

Since the Third Republic, the Panthéon has become a place to remember prominent individuals like Sadi Carnot, Jean Jaurès, and Léon Gambetta for their contributions to politics, Emile Zola, André Malraux, and Alexandre Dumas for their literary achievements, Marcellin Berthelot, Paul Painlevé, and Pierre and Marie Curie for their scientific discoveries, and even Resistance fighters who bravely fought against the Nazi occupation.

For a long time, the Panthéon was exclusively for men. The first woman to be honored, Sophie Berthelot, was inducted in 1907 only to be alongside her husband.

In 1995, the Panthéon saw the first woman inducted for her individual contributions. Marie Curie, a renowned scientist who discovered radioactivity, became the first woman to be recognized for her own achievements, alongside her husband Pierre Curie.

Honoring Women and Diversity

In recent years, there’s been a growing push to honor women and people of diverse backgrounds. In 2013, a report recommended focusing on women who embody the ideals of the French Republic. This resulted in the induction of two female Resistance fighters, Germaine Tillion and Geneviève de Gaulle-Anthonioz, along with two male Resistance fighters, Jean Zay and Pierre Brossolette.

The Panthéon welcomed another significant figure in 2018: Simone Veil, a Holocaust survivor and prominent politician.

Then came a groundbreaking moment in 2021: Joséphine Baker, a renowned artist and activist, became the first Black woman to be inducted into the Panthéon. She was also the first artist to be honored in this way.

Who Gets to Decide?

The decision of who enters the Panthéon is not a simple one. Throughout history, various entities have held the power to make this decision.

Initially, the Assemblée Constituante and later the Convention were responsible for selecting the individuals to be honored. During Napoleon I’s reign, the Emperor himself held this power.

Since the Fifth Republic, the president of France has been responsible for deciding who enters the Panthéon. President Macron has demonstrated a commitment to honoring individuals who embody the ideals of the Republic, including those from diverse backgrounds.

However, there are certain limitations. The individuals themselves or their descendants must agree to the induction. General Charles de Gaulle, for example, explicitly declined to be buried in the Panthéon, and the family of writer Albert Camus objected to his induction.

It is also possible to be inducted without having one’s remains buried in the Panthéon. This is the case for Aimé Césaire, a poet buried in Martinique, and Joséphine Baker, whose body remains in Monaco.

A Place for Greatness

The criteria for entering the Panthéon are not clearly defined, but there are unspoken expectations. The ideal candidate embodies the values of the French Republic, possesses an exemplary character, and has contributed significantly to the nation’s history and culture. Their achievements should reflect the president’s values and inspire the country.

The Panthéon is a symbol of France’s history and a testament to the enduring legacy of its heroes. It is a place where the nation acknowledges and celebrates the greatness of its individuals and honors those who have made significant contributions to its progress.