Paris, the City of Lights, enjoys a temperate climate thanks to its location on the western side of Europe and its proximity to the Gulf Stream. While the weather can be unpredictable, particularly in winter and spring, the overall climate is pleasant. The average annual temperature hovers around 12°C (54°F), with warm summers reaching an average of 19°C (66°F) in July and chilly winters averaging 3°C (37°F) in January. Although temperatures dip below freezing for about a month each year, snow falls only on approximately half of those days. The city has made significant strides in reducing air pollution and ensuring the safety of its drinking water through an effective water purification system.

Parisian Walls: A History of Growth and Change

Paris has grown significantly over the centuries, and its growth is reflected in the series of walls that have been constructed to enclose the city. The earliest wall was built on the Île de la Cité in the 3rd century CE, using salvaged stones from a Roman town on the Left Bank that had been ravaged by barbarians. This wall was rebuilt several times over the centuries, with fortified gates guarding the bridges that connected the island to the surrounding areas.

The Petit Pont (Little Bridge) leading to the Left Bank was protected by the Petit Châtelet, a fortified gate, while the Pont au Change (Exchange Bridge) to the Right Bank was guarded by the Grand Châtelet, which served as a fort, prison, torture chamber, and morgue until its demolition in 1801.

In the 12th and 13th centuries, King Philip II constructed a new wall to protect the settlements on both banks of the Seine. This wall was later expanded by Charles V in the 14th century, with the Bastille fortress guarding the eastern approaches and the Louvre fortress protecting the west.

The Grands Boulevards replaced the Charles V walls in the 17th century, with the Saint-Denis Gate and the Saint-Antoine Gate adorned with triumphal arches. The Saint-Denis arch still stands today as a reminder of this period. The Grands Boulevards, inspired by the curves of the Seine River, continue to stretch from the Place de la Madeleine in the north to the Place de la République in the east.

The Legacy of Walls and Boulevards: A City Transformed

A new wall was begun in the latter half of the 18th century, featuring 57 tollhouses that allowed the farmers-general to collect customs duties on goods entering Paris. These tollhouses can still be seen at Place Denfert-Rochereau.

The last wall, built in the mid-19th century by Adolphe Thiers, served as a true military installation with outlying forts. It encompassed several villages outside Paris, including Auteuil, Passy, Montmartre, La Villette, and Belleville.

The Industrial Revolution and the rebuilding efforts following the collapse of Napoleon III’s Second Empire in 1870 brought a surge of people to Paris. The expansion of the railway network made travel easier, and the city planner Baron Haussmann, in the period between 1852 and 1870, demolished the farmers-general walls and created wide, straight boulevards to cut through the city’s labyrinthine network of narrow streets. The 19th-century walls were eventually torn down, and the boulevards were extended in 1925.

The Heart of Paris: Île de la Cité

Île de la Cité, a ship-shaped island in the Seine, is the historic heart of Paris. This island, about 10 streets long and 5 wide, is connected to the riverbanks by eight bridges, with a ninth bridge leading to the smaller Île Saint-Louis to the southeast.

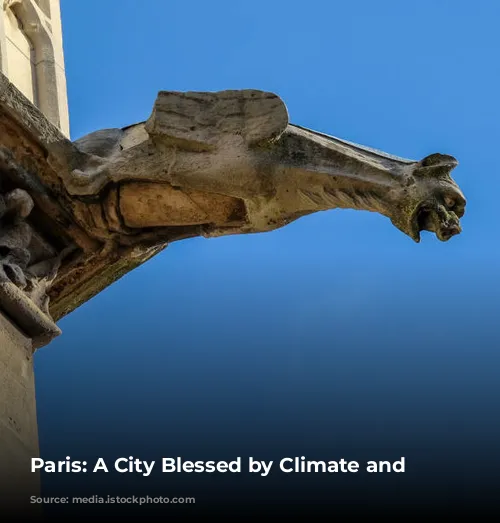

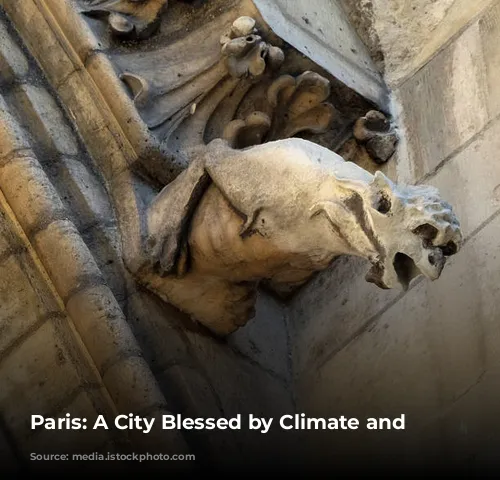

The Pont Neuf, built between 1578 and 1604, is the oldest of the Paris bridges, despite its name (which means “New Bridge”). Its sturdiness is legendary, and Parisians still use the phrase “solid as the Pont Neuf” to describe something that is incredibly strong. The bridge has five arches extending to the Left Bank and seven to the Right Bank, with its parapet corbels adorned with over 250 grotesque masks. The parapet curves out toward the water at each bridge pier, creating half-moon bays that once housed street vendors, the earliest sidewalks in Paris. For 200 years, the Pont Neuf was the main street and the heart of the city’s market. While the bridge undergoes regular repairs, the structure that stands today is the original bridge.

The tip of Île de la Cité is fashioned into a triangular park with gravel paths, flowering bushes, and benches under ancient trees. Surrounding the park is a wide cobblestone quay, a favorite spot for sunbathers and lovers. At the entrance to the Pont Neuf from the park, a bronze equestrian statue of King Henry IV stands, a reproduction of the original statue that was the first to grace a public space in Paris. Across from the statue is the narrow entrance to the Place Dauphine, named for Henry’s heir, the future Louis XIII. This square was once filled with red-brick houses trimmed with white stone, but the row of houses along its base was demolished in 1871 to make way for the Palace of Justice.

The Palace of Justice and the Sainte-Chapelle: Symbols of Power and Faith

The Palace of Justice, built on the site of the early Roman governor’s palace, was rebuilt in the 13th century by King Louis IX (St. Louis) and expanded by Philip IV (the Fair) 100 years later. Philip IV added the Conciergerie, a grim gray-turreted structure with impressive Gothic chambers. The Great Hall, the former meeting place of the Parlement (the high court of justice), was renowned throughout Europe for its Gothic beauty. Fires in 1618 and 1871 destroyed much of the original hall, and the rest of the palace was devastated by a fire in 1776. Today, the Great Hall serves as a waiting room for the courts of law housed in the Palace of Justice. The adjoining first Civil Chamber was the site of the Revolutionary Tribunal in 1793, where over 2,600 people were condemned to the guillotine. Victims were transported from the Conciergerie’s dungeons to their executions in carts called tumbrels. The Conciergerie is still standing and is open to visitors.

The Sainte-Chapelle (Holy Chapel), a masterpiece of Gothic Rayonnant style, is one of France’s most important monuments. Built between 1243 and 1248 at the behest of Louis IX, the chapel is a testament to architectural daring, with its vaulted ceilings supported by a trellis of slender columns and walls crafted from stained glass. The chapel was designed to house the Crown of Thorns, believed to be the very crown worn by Jesus during his crucifixion. Louis IX acquired the relic from the Venetians, who held it in pawn from Baldwin II Porphyrogenitus, the Latin emperor of Constantinople. Other holy relics, such as nails and pieces of wood from the True Cross, were also added to the chapel’s collection, remnants of which are now housed in the treasury of Notre-Dame.

Parisian Transformations: A City Embracing Change

In the 19th century, under King Louis-Philippe and his successor Napoleon III, a sanitization project was undertaken on the Île de la Cité. This project involved the removal of outdated structures, the widening of streets and squares, and the construction of new government buildings, including sections of the Palace of Justice. The portion of the palace bordering the Quai des Orfèvres—formerly the goldsmiths’ and silversmiths’ quay—became the headquarters of the Police Judiciaire (Judicial Police). Across the boulevard du Palais is the Police Prefecture, another 19th-century structure. On the other side of the prefecture is the Place du Parvis-Notre-Dame, an open space significantly enlarged by Haussmann. He also moved the Hôtel-Dieu, the first hospital in Paris, from the riverside to the inland side of the square. The current buildings date back to 1868.

Paris, with its grand boulevards, historical buildings, monuments, gardens, plazas, and bridges, is one of the world’s most magnificent cityscapes. In 1991, much of central Paris was designated a UNESCO World Heritage site. The city’s rich history, evident in its architecture and infrastructure, is a testament to its enduring legacy as a center of culture, art, and innovation.