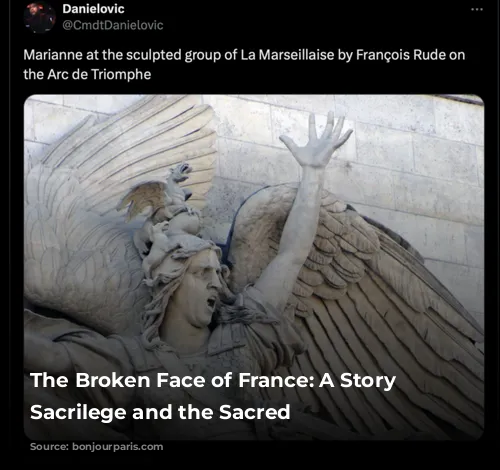

The Arc de Triomphe, a monument to French glory, stood wounded. In 2018, protestors known as the “yellow vests” shattered the statue of the Marseillaise, a symbol of France’s spirit. News outlets across the globe displayed images of her disfigured face, a gaping hole where her right cheek once was. The French government promised swift retribution for this act of vandalism. Yet, ironically, the damage seemed to silence her cry for unity and liberty.

A Broken Face Returns: Sacrilege in the National Archives

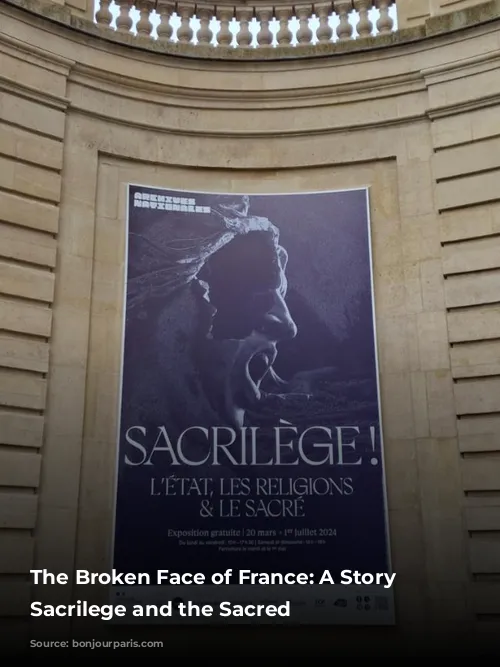

Six years later, the Marseillaise’s scarred visage reappeared, but not in the triumphant Arc de Triomphe. This time, she adorned the hallowed halls of the National Archives of France. Her presence was part of a captivating exhibit titled “Sacrilege: the State, Religions, and the Sacred”. The exhibit, a treasure trove of historical images, unveiled a timeless human struggle: the ongoing battle between the sacred and the profane. It compels us to question the very nature of sacrilege and its enduring presence throughout history.

The Rise of Sacrilege and the Medieval World

In antiquity, condemnation for acts of sacrilege was rare. But with the dawn of the Middle Ages, the notion of sacrilege exploded. This rise can be attributed to the deep-seated belief that a kingdom’s stability rested on the foundation of a unified faith. This rigid conviction, often wielded like a weapon, extended even to those who swore to protect the sacred. The Knights Templar, tasked with defending Jerusalem and pilgrims bound for the Holy Land, found themselves accused of heresy. The National Archives exhibit showcases a chilling document from 1307, a record of the inquisition against the Knights Templar, a testament to the harsh consequences of challenging the dominant religious order.

The Papal Bull and the King’s Crusade

The French monarchs of the Middle Ages took the concept of religious uniformity within their realms very seriously. Pope Innocent III, in the early 13th century, initiated a crusade against the Cathars, a dissenting Catholic group in Southern France. This brutal campaign, aimed at achieving a utopian unity of faith, proved to be a double-edged sword. In 1268, Pope Clement IV, recognizing the excesses of the persecution, issued a papal bull urging King Louis IX to ease his relentless pursuit of religious homogeneity. The bull itself, a historical artifact, is displayed at the National Archives, offering a glimpse into the complex interplay between religious authority and political power.

The Sacred and the Profane: A Wall of Authority

The exhibit revealed that as centralized states emerged, they erected a formidable wall around the “sacred.” Any act that challenged what the state deemed holy was deemed an infraction. The sacred became synonymous with royal power, the doctrines of the Catholic Church, the divinely ordained order of society, and even any hint of independent thought, questioning of authority, or “sacrilege.” This newfound power structure prohibited any individual from questioning the “sacred.” In fact, it was the duty of both royalty and the Church to quell any threat to its sanctity.

The Birth of Blasphemy: A Weapon of Divide

As the Church and state merged into a single entity across Western Europe, the concept of blasphemy became the key term defining the chasm between the sacred and the profane. The Reformation era witnessed the exploitation of this term, with Catholic powers labeling everything Protestant as “blasphemous” and vice versa. Propaganda, a powerful tool of the time, fueled hatred and justified acts of violence. The exhibition features a captivating book, “Les Sorceleries de Henri de Valois (The Sorceries of Henri of Valois)”, showcasing the manipulation of accusations of blasphemy for political ends. This book paints a monstrous portrait of Henri III, a French king who flirted with Protestantism and embraced a lifestyle deemed “libertine”.

The Legacy of Sacrilege: A Shifting Definition of the Sacred

While the prosecution of blasphemy declined over the centuries, its legacy lingered. In 1766, the Chevalier de la Barre was executed for his “blasphemous” actions, a stark reminder of the potency of this charge. This tragic incident ignited a wave of condemnation from intellectuals like Voltaire and sparked outrage among informed individuals. The exhibit features de la Barre’s letter of condemnation, a powerful artifact that reflects the absurdity of such charges.

The Enlightenment, however, brought about a shift in how the sacred was defined. Blasphemy as a punishable offense was deemed outdated. France, however, did not abolish the sacred entirely; it merely transferred its focus. The state, and its leaders, were now elevated to a sacred status. The exhibition reveals the hypocrisy of this transition, highlighting the 1814 declaration proclaiming the king “inviolable and sacred” and the repeated lawsuits filed against a cartoonist in 1830 for satirizing King Louis-Philippe.

The Sacred and the Present: A Complex Landscape

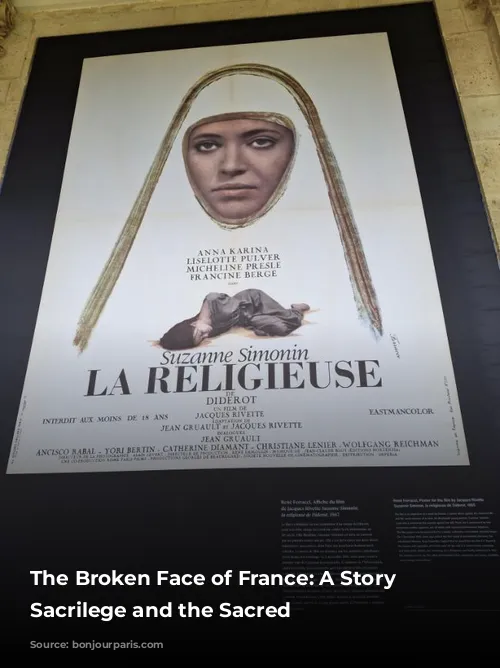

The exhibit delves into the ongoing challenges posed by the sacralization of institutions and individuals in the 20th century. It confronts us with questions surrounding the tension between free speech and the sanctity of beliefs, the boundaries of personal offense, and the freedom of creative expression, even when it satirizes or exposes the “sacred.” The exhibit features a poster of Diderot’s novel-turned-movie, “La Religiuese” (The Nun), which caused a public uproar and was subsequently banned by the minister of information in 1965. This captivating story underscores the enduring struggle to balance the sacred and the profane in our modern world.

Conclusion: The Sacred Continues to Haunt Us

The “Sacrilege” exhibit serves as a potent reminder that the conflict between the sacred and the profane remains a fundamental aspect of human experience. From the medieval crusades to the modern debates on free speech, the definition of the sacred has shifted, yet the tensions surrounding its protection endure. The broken face of the Marseillaise, a symbol of French identity, serves as a poignant reminder of the fragility of sacred values and the consequences of treating them as inviolable. As we navigate the complexities of the 21st century, the exhibit urges us to reflect on our own understanding of the sacred and its impact on our society.