The Eiffel Tower, a symbol of Parisian grandeur, wasn’t always embraced. Before its construction and for two decades after its completion, the Iron Lady faced criticism and doubt. This article explores the battles Gustave Eiffel endured to bring his vision to life and the controversies that surrounded the Tower’s existence.

A Towering Rivalry

Gustave Eiffel’s journey to build his iconic structure was far from smooth. In the lead-up to the 1889 World’s Fair, the idea of a monumental tower was gaining traction. France aimed to celebrate the French Revolution’s centennial, unite its people, and showcase its engineering prowess to the world. Eiffel’s competitor, Jules Bourdais, a renowned architect, proposed a granite and porphyry tower named the Sun Tower, boasting a towering 1,200 feet.

The battle lines were drawn: Iron vs. Stone, Engineer vs. Architect, Modern vs. Classic. Eiffel emphasized his ability to construct his tower within budget and timeframe, touting its scientific and defensive applications. Bourdais, on the other hand, faced skepticism about the feasibility of such a towering stone structure.

In 1886, Bourdais seemed poised for victory, gaining support from the new Prime Minister. But Eiffel, never one to surrender, persuaded the Minister for Commerce, Edouard Lockroy, of his tower’s merit. Eiffel offered to finance the entire project in exchange for operating rights, swaying Lockroy’s decision.

The competition for the World’s Fair attractions included a specific request: a 1,000-foot iron tower with a 410-foot square base. This seemed tailor-made for Eiffel’s vision. Bourdais, caught off guard, adapted his Sun Tower, replacing stone with iron, but ultimately, Eiffel’s project was chosen.

Resistance and Rebuttals

Eiffel’s victory was just the beginning of his challenges. Architects were outraged at the selection of an engineer for such a prominent project. Paris’s artistic community erupted in protest as construction began.

In 1887, a “Protest against the Tower of Monsieur Eiffel” was published in Le Temps newspaper, signed by prominent figures in the arts and literature. They labeled the tower a “useless and monstrous” structure, an “unworthy blight on Paris’s beauty.”

Eiffel responded to these criticisms with conviction. He argued that the tower’s structural strength, dictated by its resistance to wind forces, contributed to its inherent beauty. He embraced the monumental scale, claiming it possessed a unique charm.

Public Opinion: From Doubt to Delight

The construction of the Eiffel Tower ignited contrasting opinions among Parisians. Many questioned the aesthetics of the towering metal structure under construction. Artists, already critical, fueled the public’s reservations, labeling the tower a “belfry skeleton,” a “tragic street lamp,” and a “mast of iron gymnasium apparatus.”

Even the esteemed author, Guy de Maupassant, expressed his disdain, calling it a “giant ungainly skeleton” and a “ridiculous factory chimney stack.” His aversion was so strong that he claimed to dine on the Tower’s first floor, as it was the only place in Paris where he couldn’t see the structure.

Despite the criticism, the Parisian population’s alleged hatred of the Tower lacked substantial evidence, except for concerns among Champ de Mars residents. A local council member threatened legal action, prompting Eiffel to personally assume all construction risks and offer compensation for any accidents. Fortunately, no such incidents occurred.

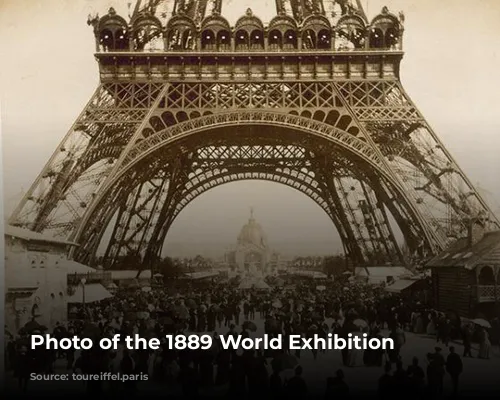

On May 15, 1889, the Tower opened to the public, greeted with overwhelming enthusiasm by crowds of French and international visitors. The controversy faded, replaced by widespread admiration. Some of the initial critics even offered public apologies. The Tower became a symbol of Parisian pride and modernity, an icon of the city.

A Monument Saved

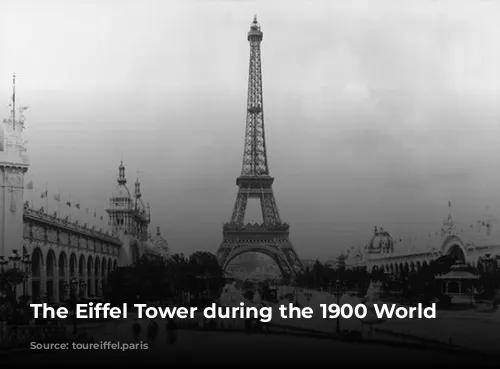

Despite the Tower’s widespread acceptance, some detractors, like architect Charles Garnier, remained opposed. In 1894, a call for projects for the 1900 World’s Fair included proposals to modify or even demolish the Eiffel Tower. While several outlandish ideas were proposed, none were selected, and the Tower remained intact.

However, the Tower’s fate hung in the balance. The operation contract granted to Eiffel was set to expire in 1909. Visitor numbers dwindled, and the Paris City Council considered demolishing the Tower as part of a Champ de Mars redevelopment plan.

Eiffel, determined to preserve his creation, championed scientific research conducted on the Tower. Meteorological observations, wireless telegraphy experiments, and studies on falling bodies and aerodynamics took place on the world’s tallest structure.

The Tower’s strategic value played a vital role in its survival. In 1903, Captain Gustave Ferrié, with Eiffel’s support, installed a military network of wireless telegraphy on the Tower. The increasing range of this technology highlighted the Tower’s strategic importance, as it could transmit and receive long-distance signals.

On January 1, 1910, Eiffel’s contract was renewed for 70 years. The Eiffel Tower was saved, securing its place in the Parisian landscape for generations to come.

The Eiffel Tower stands as a testament to Gustave Eiffel’s vision and determination. From its controversial beginnings to its status as an iconic symbol of Paris, the Iron Lady has endured, captivating visitors from around the world.