The Eiffel Tower, a Parisian icon, has always been shrouded in mystery and intrigue. Some believe its graceful “A” shape is a subtle tribute from Gustave Eiffel to his childhood sweetheart, Adrienne. This romantic narrative, however, is a fictional device used in the 2021 film aptly titled “Eiffel,” starring Romain Duris.

While this romantic twist adds an element of intrigue, is it truly necessary to embellish the story of the Iron Lady? The film is far more convincing in portraying the sheer magnitude and technical prowess of the construction project. Built in a mere two years, the tower was inaugurated on March 31, 1889, to serve as the centerpiece of the Paris Universal Exhibition, commemorating the centenary of the French Revolution.

A Tower Reaching for the Sky

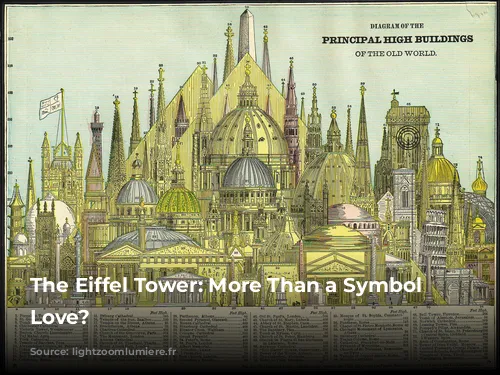

The documentary “Eiffel, la guerre des tours” (available on Arte until January 16, 2024) sheds light on the origins of the Eiffel Tower. In the late 19th century, the tallest tower stood at a mere 169 meters. The American capital’s obelisk, dedicated to George Washington, the first president of the United States, took nearly 40 years to build due to the Civil War and technical challenges. By 1884, this monument slightly surpassed the Great Pyramids of Egypt and the spires of Gothic cathedrals.

The prevailing trend, however, was to aspire for greater heights, reaching 1,000 feet, or approximately 300 meters. This ambitious goal served as the foundation for the 1889 Universal Exhibition competition, attracting 107 entries.

A Battle of Designs

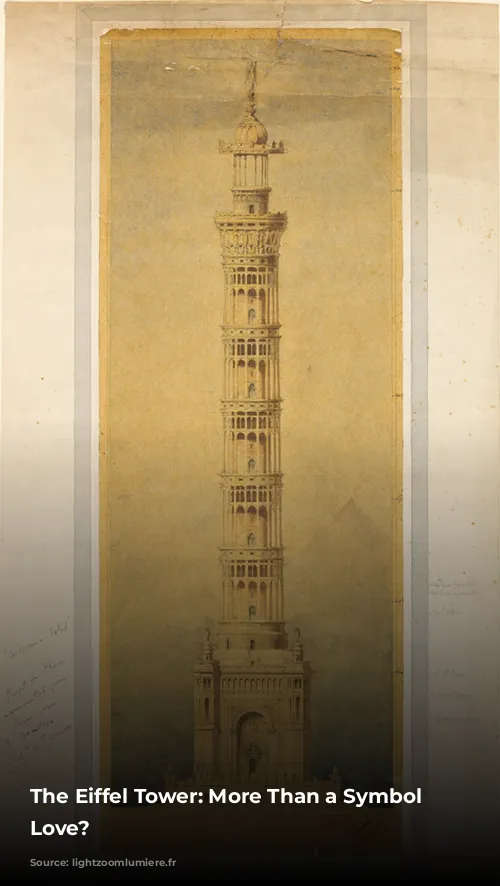

The most formidable competitor to Eiffel’s vision was the project of architect Jules Bourdais, who had previously designed the Trocadero Palace for the 1878 Paris Universal Exhibition. His creation would stand face to face with the Eiffel Tower until its demolition in 1935, replaced by the Palais de Chaillot.

Bourdais envisioned a towering granite structure, reaching 360 meters, adorned with stacked galleries and surrounded by columns. The architect may have underestimated the extensive foundation work required to support such a massive tower.

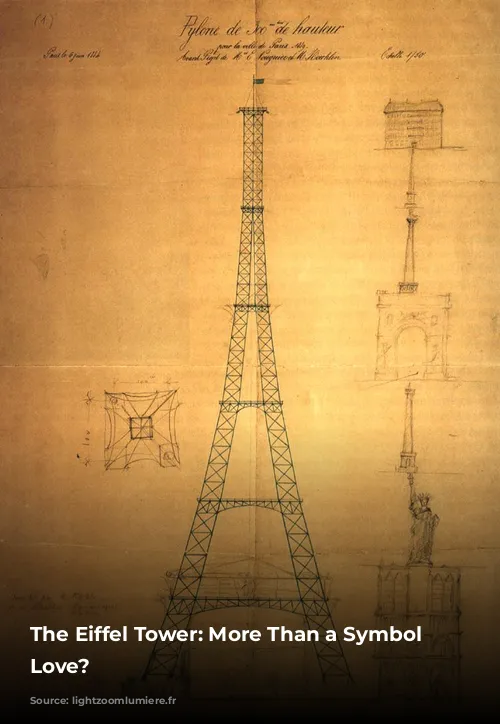

Meanwhile, for the Eiffel Company, engineer Maurice Koechlin sketched an initial, rather rudimentary design for a 300-meter-tall iron pylon. Engineers meticulously calculated its feasibility, particularly its ability to withstand wind forces. Ultimately, architect Stephen Sauvestre finalized the shape of the future Eiffel Tower.

This rivalry between Bourdais and Eiffel symbolizes the clash between a traditional architect and a more forward-thinking engineer. Both sought political support, and Eiffel’s victory was largely due to the Minister of Industry and Commerce, who crafted the competition guidelines to favor his design.

The Moonlight Tower: Illuminating the Night

Today, our over-illuminated cities strive to “save the night.” But in the late 18th century, with the rise of public lighting, the utopian dream was quite the opposite. Why illuminate just a few street segments when you could bathe an entire city in light by placing light sources atop towering structures?

Jules Verne, in his 1860 novel “Paris au XXe siècle,” envisioned a lighthouse in the port of Grenelle, “piercing the sky to a height of five hundred feet. It was the tallest monument in the world, and its lights reached forty leagues; they could be seen from the towers of Rouen Cathedral.”

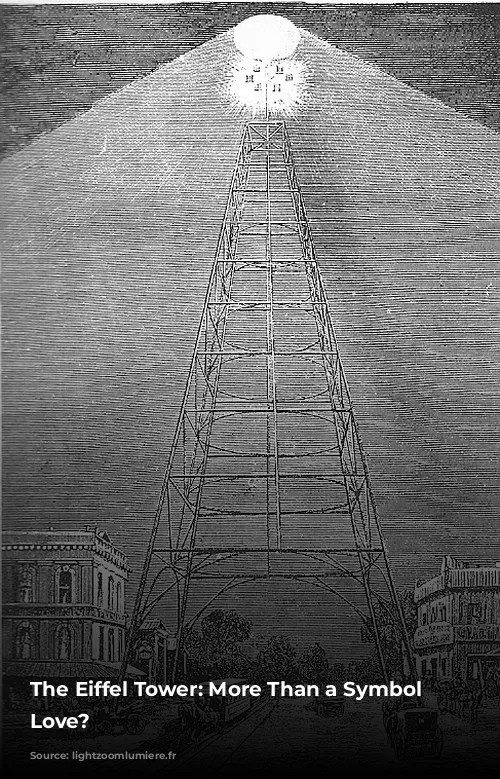

However, the existing light sources lacked the necessary power. The solution emerged with the advent of arc lamps, whose intense light stunned audiences. By the early 1880s, several American cities, including San José, had constructed these “sun towers,” reaching several tens of meters high. The stable, white light emitted by the arc lamps resembled that of a full moon, leading to their designation as Moonlight Towers.

Inspired by a study trip to the United States, French engineer Amédée Sébillot partnered with Bourdais to transform his tower into a Colonne-Soleil. With a height 5 to 7 times greater than its American counterparts, the proposed structure required 25 to 50 times more power to achieve the same illumination level on the ground (due to the “inverse square law”). The project called for a single focal point with 100 arc lamps arranged in a 12-meter-diameter ring, capable of illuminating an area with a radius of 5 kilometers. Reflectors scattered throughout the city were even intended to direct light into homes. At the time, these luminous intrusions were considered a sign of progress.

Illuminating Paris from the Eiffel Tower

To secure victory in the competition, Gustave Eiffel needed to convince everyone that his tower would be more than just an ornate monument. He envisioned conducting scientific experiments on the third floor, and, with no apparent hesitation, adopted his competitors’ idea of illuminating Paris. In practice, this lighting function would be more modest, involving a lighthouse at the tower’s peak and two rail-mounted projectors on the third floor.

The projectors emitted highly directional beams with an intensity of 8 million carcels. This was the unit used for measuring luminous intensity at the time, roughly equivalent to 10 candelas. At night, operators directed the beams towards various landmarks in the city, creating a captivating illumination display. Imagine, for example, directing the light towards the Sacré-Cœur Basilica, then under construction. Located 4.7 kilometers away as the crow flies, it would receive a few lux of illumination, sufficient for visibility on a moonless night. However, the beam’s division would likely be disappointing.

A Beacon in the City

Ultimately, only the lighthouse’s light remains atop the Eiffel Tower. In 1889, a power output of 500 horsepower, or about 370 kW, was required. The emitted light would have been visible as a bright spot from the heights of Chartres Cathedral (75 kilometers away) and Orléans Cathedral (115 kilometers away). Inaugurated in the year 2000, the current lighthouse consists of 4 projectors equipped with xenon arc lamps, providing a total power output of 24 kW and a claimed range of 80 km. Numerous tall towers have also incorporated lighthouses for air navigation.

However, the utopia of bringing light to all, including the poorest outskirts, left many contemporaries skeptical of the Moonlight Towers. Due to ultimately disappointing illumination and practical difficulties, this idea was quickly abandoned at the dawn of the 20th century. Only the city of Austin, Texas, retains a few Moonlight Towers. While they add a touch of poetry to urban nights, these vestiges primarily serve as a reminder that this solution is not suitable for public lighting.

Eiffel, la guerre des tours, documentary on Arte

* Yann Toma: Human Energy at the Eiffel Tower in the face of the climate emergency

* Pierre Bideau, lighting designer for the Eiffel Tower from 1985 to 2003